The area of Lake Plastira and the Agrafa mountains has a long history dating back to ancient times that continues to the present. This uninterrupted historical progression is conveyed through legends and traditions and can be discovered along every step through the region.

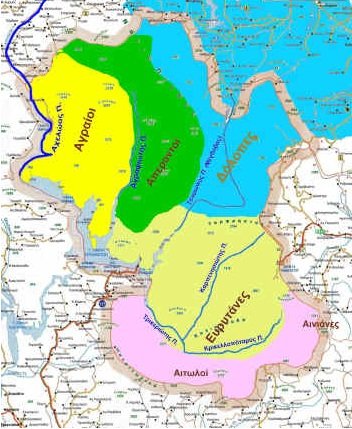

Dolopes

In ancient times, the area’s inhabitants were the Dolopes, an ancient Greek tribe that lived around the Agrafa mountain range. Their main city was Ktimenion, where the village of the same name survives. Until the 6th century BC, the Dolopes remained autonomous. Then they came under the dominion of Thessaly and Aetolia. They participated in many campaigns, as well as in the Trojan war. In 374 BC, they were subjugated by the tyrant Jason of Ferres, while in 344 BC they were allied with King Philip II of Macedon, father of Alexander the Great. Later, they became part of the Aetolian League until 168 BC, when they were conquered by the Romans. According to Pausanias, the tribe became extinct in the 2nd century AD.

Agrafa

The Agrafa mountain range is an area of great historical interest. Agrafa forms the southern end of the Pindos range; it occupies the entire northern part of the Prefecture of Evritania and the western part of the Prefecture of Karditsa, known respectively as the Evritanian and the Thessalian Agrafa. The Thessalian Agrafa with its 73 villages is the northern part of the mountain range, home to the range’s highest peak, Karaba (2,021m) and Lake Plastira, while to the east it rolls down into the Thessaly plain. The history of Agrafa is ancient. From 1500 to 27 BC it was inhabited by the Dolopes and the Athamanes, who developed their own culture. Later, they were involved in the conflict between Macedonians and Romans, and during the Middle Ages they were overrun by waves of Northern peoples: Slavs, Albanians, Vlachs, etc.

During the Ottoman occupation of Greece, the region of Agrafa flourished, particularly after it was granted autonomy by the Ottomans with the signing of the famous “Tamasi” Treaty of 1525, which is the oldest text of its kind. This Treaty recognized the autonomy of the villages of Agrafa, and despite their obligation to pay an annual tax, it gave rise to a time of great economic growth. Large churches and monasteries were built, the art of hagiography flourished, schools and colleges were built and many scholars were active in the region. The freedom that prevailed drew many fugitives from the Ottoman rule who formed bodies of “kleftes” (rebels) along with local chieftains, like Katsandonis and Georgios Karaiskakis, the most prominent leader of the 1821 Greek revolution, who led the rebel uprising of Agrafa until 1824.